By Jack Rogers | Chiropractor & Director of Clinical Operations, Pinnacle Spine & Sports

For a long time, ‘core strength’ has been a catch phrase in the rehabilitation, health and fitness industries as a counter to the increasing incidence of spinal pain over the last 20 years.

However, even a cursory review of present-day neuroscience literature will rapidly expose the differences of opinion that exist about the role of exercise in rehabilitation.

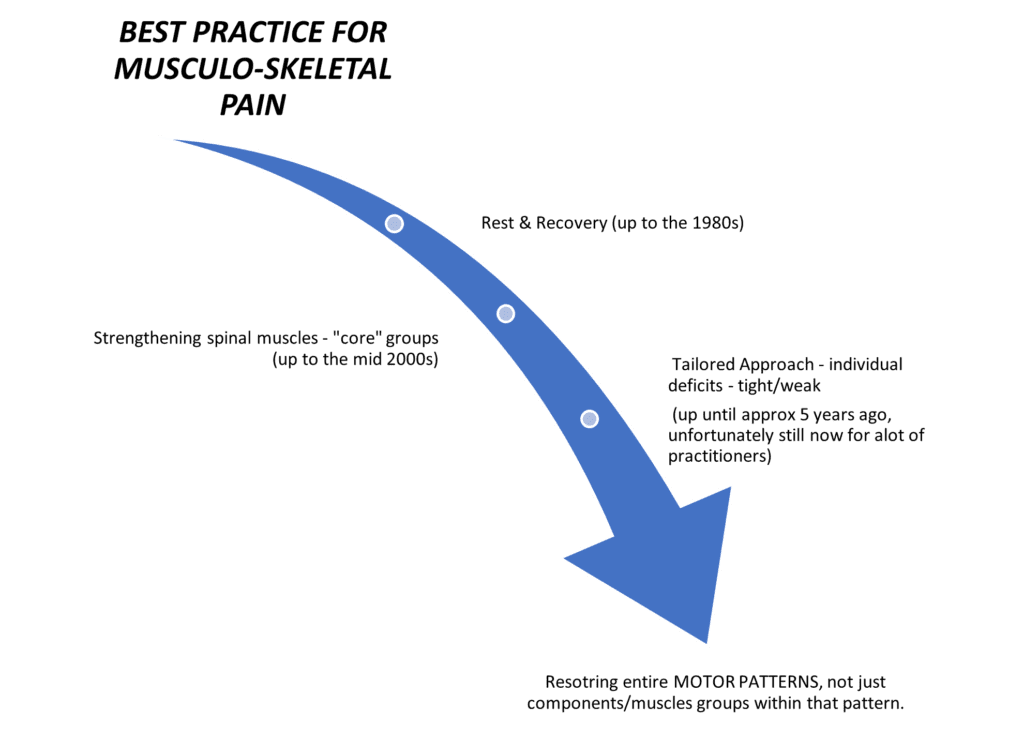

Accepted management of musculoskeletal pain has evolved over recent decades. The initial model emphasising rest and recovery made way to methods of strengthening spinal muscles, particularly the so-called ‘core’ groups. This core strength paradigm was subsequently refined to a tailored approach, in which specific exercises were individually devised for the deficits that a particular patient might present with.

But have all these paradigm shifts enhanced treatment outcomes for patients in pain? Maybe not.

There is now a growing trend of discontent in current literature with tailored exercise programs. We are beginning to re-evaluate of our thinking about how exercise affects musculoskeletal pain patients. Our attempts to specifically target individual muscles that are deemed to be functionally under or over-active does not appear to improve outcomes.

The human brain stores motor patterns in terms of desired functions (such as walking, writing, or kicking a soccer ball). This being the case, targeted exercises that aim to strengthen the gluteus maximus, or activate the transverse abdominus, or strengthen our ‘core’ while lying on an exercise mat, do not seem to help the next time we go for a walk, or bend to pick something off the floor.

In essence, the human brain needs to practice performing these real-world functional movements and not the individual sub-components of a larger activity.

This is why we utilise a real-world, functional approach to exercise – coupled with a comprehensive education program. Your brain needs to ‘un-learn’ poor patterns for movement and re-train the correct neural pathways in order to learn a new one. Once correct movement is restored, so is normal function in our tissues.

References:

- Long, M ( 2016). Is Walking Enough?(or, why do we over-think things). Cdi.edu.au

- Garrick, J. G. (2014). Core stability: a call to action. Clin J Sport Med, 24(6), 441. http://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0000000000000152

- Vasseljen, O., Unsgaard-Tøndel, M., Westad, C., & Mork, P. J. (2012). Effect of Core Stability Exercises on Feed-Forward Activation of Deep Abdominal Muscles in Chronic Low Back Pain. Spine, 37(13), 1101–1108. http://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e318241377c

- Smith, B. E., Littlewood, C., & May, S. (2014). An update of stabilisation exercises for low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 15(1), 416. http://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-416

- Mannion, A. F., Caporaso, F., Pulkovski, N., & Sprott, H. (2012). Spine stabilisation exercises in the treatment of chronic low back pain: a good clinical outcome is not associated with improved abdominal muscle function.European Spine Journal, 21(7), 1301–1310. http://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-012-2155-9